(with memories from Laura Mulvey)

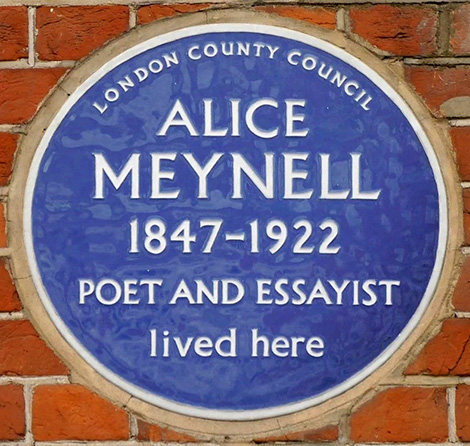

47 Palace Court, which at the time of writing is undergoing conversion by FNFC Architects into four flats, was built in 1888-89 for the Meynell family. The Meynells, Alice and Wilfrid, were important figures in the London literary world, as were some of their children. While Wilfrid was a prolific journalist, editor and publisher who became a doyen of the British Catholic literary world in particular, Alice was the major author in the family: a poet, essayist and literary critic of very distinctive talents, who was seriously proposed for the role of Poet Laureate on two occasions. She was President of the Society of Women Journalists and Vice-President of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League. Bayswater residents may have seen her name on the blue plaque at Palace Court.

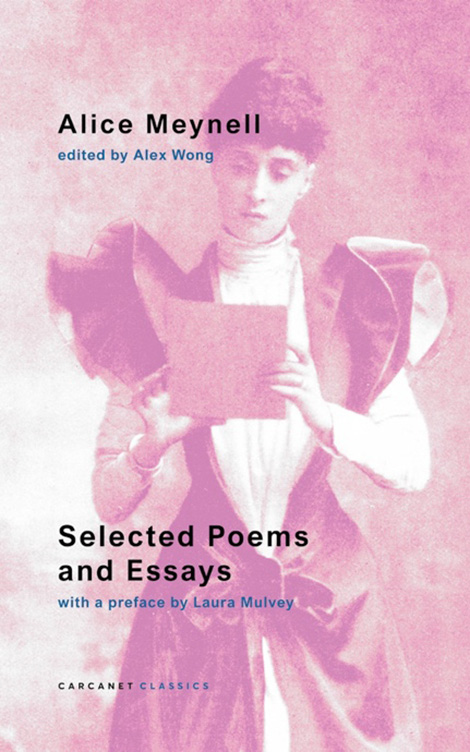

The recent publication of my edition of Alice Meynell’s Selected Poems and Essays, coinciding as it does with the beginning of works to the Palace Court house, gives me occasion to write a few words for Bayswater residents about this exceptional author, her family and her life in the area.

Alice Meynell (née Thompson) was born in Barnes, Surrey (now London), in 1847 to a middle-class family of artistic and intellectual persuasion. Her mother, Christiana, was a talented pianist doted upon by Charles Dickens; she gave up a musical career when she married. Thomas Thompson, Alice’s father, was brought to England as a child from Jamaica, where his father and grandfather had owned sugar plantations. Thomas is traditionally thought to have been educated at Cambridge (although records are lacking), and later was able to support his family on the inheritance from his grandfather. His mother (and therefore Alice’s grandmother), Mary Edwards, is described as ‘Creole’ and was of mixed race. Alice and her sister Elizabeth or ‘Mimi’—later Lady Butler, a celebrated historical painter—were brought up in somewhat Bohemian style, mainly in Italy and on the Isle of Wight.

In 1868 Alice, following her mother’s example, converted to Roman Catholicism—and fell in love with the young and cultivated Jesuit priest who received her into the Church. A painful break in their friendship was required, and this impossible love inspired several of Alice’s passionate early poems. Her first volume of verse, Preludes, was published in 1875 with illustrations by her sister.

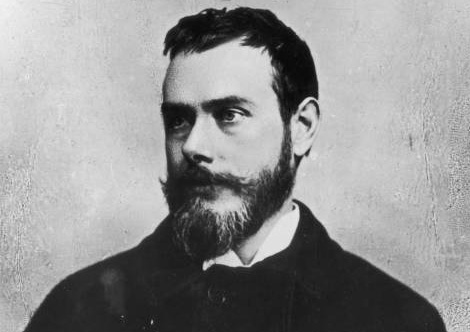

In the following year she met Wilfrid Meynell (the name rhymes with ‘fennel’), a young journalist and fellow Catholic convert who wrote to her in admiration after having read a review of Preludes. They married in 1877. Alice and Wilfrid worked both jointly and independently on various journalistic tasks, co-editing and copywriting for several periodicals as well as writing literary and critical essays, signed and unsigned, for others.

They had eight children, of whom one died in infancy. Several of the Meynell children became involved in literary life. The best known are Viola Meynell, an author of fiction (and her mother’s first biographer), and Francis Meynell, a poet and left-wing newspaper editor, who co-founded the Nonesuch Press.

In 1888 the Meynells, then residing at Phillimore Place, Kensington, had bought a plot of land in Bayswater using the inheritance from Alice’s father, and the building was rather quickly built to their specifications. Leonard Stokes, the architect they selected, was a fellow Roman Catholic whose designs took an Arts and Crafts aesthetic of variable intensity towards both neo-Gothic (especially for religious buildings) and neo-Georgian or Queen Anne styles. He did a good line in telephone exchanges, which fall into the latter category; his exchange building, for instance, on Gerrard Street (now the main drag in London’s Chinatown) was much more exciting than the 1930s replacement that still stands, while a more modest but elegant Georgian one on Gilmore Street, Lewisham, has lately undergone the same fate as that in the offing for 47 Palace Court, having been converted into luxury apartments in 2014.

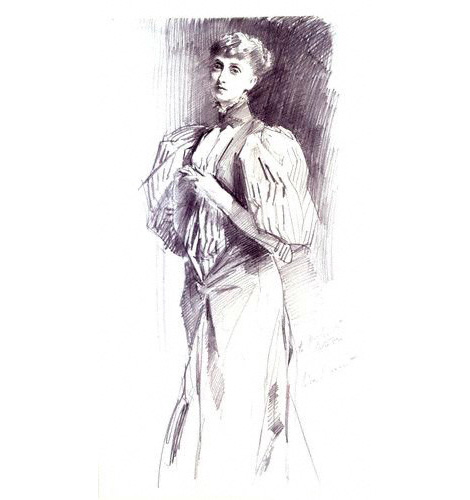

Leonard Stokes was the brother of the painter Adrian Scott Stokes, who had painted the watercolour portrait of a young Alice Thompson (still in possession of the family) that was later used for the engraved frontispiece in editions of her work.

The house Leonard Stokes designed for the Meynells is described in an advertisement of 1906—by which time Alice and Wilfrid, now most of the children were grown up, no longer needed such a large home—as having a front elevation ‘of brick and stone in the Flemish style’. It is an elegant example of the Gothic-free side of Aesthetic Movement architectural taste. The Pevsner guide credits it with ‘much personality’.

It was in fact one of the first houses in the area to be built, and at first, before the terrace was extended, was known simply as ‘Palace Court House’. Later, as neighbouring homes appeared, it was assigned the street number 47.

Alice and Wilfrid worked long hours in their new library. Although Alice would work alone upstairs on her more serious, artistic work, the relatively routine tasks of copywriting, proofreading, etc., which came in a steady stream for these two busy journalists, were conducted together in the library—where visitors, if they respected the necessary silence, were sometimes admitted. As their journalistic work was silently performed at a shared desk, the children would sometimes sit on the floor beneath them and work on their own ‘magazine’, in which, among other things, they would review their mother’s work. But another regular presence in the library, sometimes interrupting, sometimes working quietly at the same table, was the Catholic poet and critic Francis Thompson, whose poem ‘The Hound of Heaven’ is a classic of English religious verse.

To many modern readers, the Meynells are remembered mainly for being the protectors and advocates of Thompson, who was a homeless laudanum-addict when they discovered him and began to publish and promote his work. The Meynells supported him financially, too, a commitment that lasted for the rest of his life. Thompson was a highly eccentric character, a religious visionary and obsessional writer who struggled to get the better of his addiction and take care of his frail health. The Meynells found him lodgings quite close to their Palace Court home, where he was for long periods a daily presence.

Also a regular dinner guest for a time, until his passionate affection for Alice necessitated a break in their friendship, was another major Catholic poet of the period, Coventry Patmore, whose work she always celebrated.

Sundays at Palace Court were days for visitors, and the visitors—not only friends, associates and admirers of Alice and Wilfrid, but also, as time went on, younger friends brought by the children—were many and varied. Among those mentioned by Viola Meynell are Oscar Wilde, the Decadent artist Aubrey Beardsley, the poet and critic Lionel Johnson (whose most famous poem today is ‘The Dark Angel’), the publisher John Lane, the Irish poet W. B. Yeats, and another Irish writer, Katherine Tynan, who lived not far away in Notting Hill. Special mention is made of the poet Agnes Tobin, ‘a beautiful Californian friend of my mother’, who ‘began in 1896 to increase the number of our visitors by more than her own presence, our other friends finding themselves unable to forgo the chance of seeing her’. It was with Agnes Tobin, and at her suggestion, that Alice Meynell travelled to and around the USA in 1901-02, where she undertook an extensive lecture tour, becoming stranded there for longer than anticipated owing to Tobin’s delicate health.

Viola Meynell also offers a description of the Palace Court drawing-room, where Sunday guests were received: ‘a pleasant room for a gathering; it was beautifully proportioned; it was panelled with old Japanese gold-thread embroideries, and a little collection of Venetian glass was bestowed on an inlaid Spanish table that had belonged to Lord Leighton’. Of her mother’s attitude to her varied and often illustrious guests, Viola tells us: ‘It was so inconceivable to her that everything should not be suitable for the entertainment of anyone who came that she offered even very plain hospitality with the slight ceremony that went with the assumption that it was good’. The implication of this nicely phrased remark is confirmed by Francis Meynell, who records that even his namesake, Francis Thompson, who (remember) had lived a hard life of vagrancy with few material luxuries, found it necessary to tell Wilfrid one day: ‘Wilfrid, the Palace Court food is shocking’.

The Meynells lived at Palace Court from 1889 to 1905, when Wilfrid, who worked at the Catholic publishers Burns and Oates, arranged for the vacant space above the firm’s offices to be converted into apartments. From the spacious Palace Court house—four storeys, a gabled attic and basement—they moved into the new, top-floor flat, in which great ingenuity was used to make the most of rather limited space. (A lift was later installed, which landed visitors in the Meynell bathroom. One assumes this will not be the case with the new lift proposed for the Palace Court redevelopment.) The Granville Place flat was situated on the corner with Orchard Street, just off Oxford Street: as far as I can work out, on the site of what is now the Oxford Street branch of Marks and Spencer. Selfridges would have been an obtrusive new neighbour a few years after their arrival.

The Palace Court property, meanwhile, was rented out and helped to supplement the Meynell family income. In 1911 the Meynell family acquired a larger house and grounds at Greatham, Sussex, which eventually became Alice and Wilfrid’s main home in their latter years and remains in the family today.

Alice Meynell died in 1922 at the age of seventy-five, while Wilfrid lived to be ninety-five and died in 1948, still at Greatham.

At this point the story is taken up by the film critic and feminist theorist Laura Mulvey, a great-granddaughter of Alice and Wilfrid, who has contributed a preface to the new anthology. In Wilfrid’s later years, Laura explains, Palace Court came back into family use. During the 1930s it was occupied by some of Wilfrid and Alice’s grandchildren who had recently left University and were working in London. These included Sylvia and Christiana Lucas (daughters of the Meynell’s daughter Madeline) and Elizabeth Sowerby (daughter of Olivia), perhaps with other relatives and friends. ‘I do know they had large parties in the Drawing Room’, Laura writes; ‘I have Sylvia’s (my mother’s) accounts of expenditure and the guest lists. As I understand it, guests paid a very small contribution to expenses which were alcohol—gin, whisky and beer, plus ginger ales, etc.—boxes of cigarettes and hire of a gramophone for dancing.’ I will give the rest in Laura’s words:

I lived at Greatham with my grandmother, Madeline, from my birth in 1941; my mother went on working, living at 47 Palace Court, until my sister Rosamund was born in 1943 when she joined us at Greatham.

Just before and during the war, the number of W&AM great-grandchildren had increased, and in its immediate aftermath 47 Palace Court provided a much-needed home for some of the families during these quite difficult times. From the top of the house:

Barbara Wall (Madeline’s youngest daughter) with husband Bernard and daughters Gabriel and Bernadine lived in the attic, occupying former maids’ and ‘help’ floor. This floor was separated from the rest of the house with its own staircase.

Hermia Eden (Olivia’s oldest daughter) with husband Peter and sons Jonathan and Sebastian, and daughter Miranda, lived on the next floor down, occupying former family bedrooms.

Grazia Meynell (Everard’s widow) lived either in the Library or the Drawing Room with the other occupied by a family friend (possibly Colin Shand).

Sylvia Mulvey (Madeline’s eldest daughter) with husband Charles and daughters Laura and Rosamund lived on the ground floor, with the former Dining Room as their sitting room (with tiny kitchen built into the well) and former Morning Room as their bedroom. I think the bathroom (leading off the hall) must have been part of the original design. The elegant staircase led down to a spacious front hall, where Rosamund and I spent a lot of time, practising our dancing and acrobatics. There was a pay-phone (Press Button A/Press Button B), that served the whole house.

George and Adelaide (caretakers) lived in the basement. George looked after the boiler and general maintenance; Adelaide probably did some cleaning. I think they had been at 47 for many years and were very friendly.

There was a small, rather gloomy, back garden (known as ‘backy yard’) where Rosamund and I played occasionally—but it lacked appeal.

At weekends we [children] went to Kensington Gardens where we played in the Children’s Playground, walked round the Round Pond and generally rambled about. This was immense fun and makes an important contribution to my memories of this time. Rosamund and I also went for walks in Kensington Gardens with our parents. I loved the Dutch Garden (with its beautiful ‘tunnel’ of arched branches) and also, very particularly, the Orangery, which has remained my idea of architectural beauty to this day.

After WM’s death in 1948, it was decided to sell 47. So far as I remember, my great-uncles Murray Sowerby and Francis Meynell were responsible for this. My grandmother was bitterly opposed to selling and her four granddaughters then composed letters of protest to Murray and Francis—probably never sent, but certainly reflecting Madeline’s view. The house was finally sold to The White Fathers, for a sum that those opposed to the sale thought inadequate, and rumours later circulated that Murray and Francis had thought that there was no future in London property. (This might well not be fair on them but the rumour definitely circulated.)

The Meynell descendants moved out of Palace Court in 1950, Laura’s immediate family moving to Clanricarde Gardens, two streets to the west of Palace Court. The White Fathers, a Catholic society, remodelled the interior and occupied the building for the next dozen years. Laura adds a postscript:

Although both our parents were so-called ‘lapsed’ Catholics, Rosamund and I were brought up as Catholics due to the strong influence of our grandmother. When we had our First Communion in the early 1950s, Madeline (or perhaps Barbara) arranged for it to take place in 47, where the White Fathers had converted the Library into a Chapel. This was a very moving return to the house (enhanced no doubt by the ceremony!) and it was the last time I was there.

In 1963 the house passed into the ownership of another Catholic religious group, the Vincentian Fathers or Congregation of the Mission, a part of the ‘Vincentian Family’ of organisations inspired by the work of St Vincent de Paul. Again remodelled, as the planning documents show, the building was used by them until it was sold in 2021 for a sum beginning with the number 6, at which point the planning application was submitted for the renovation and redevelopment work that is currently in progress and scheduled for completion in 2028. The ‘Heritage Statement’ prepared at that time by Montagu Evans indicates that the interior had been substantially pulled about since the Meynells’ day, so that little of material historical value remains behind the elegant façade. Work to the interior will be significant, and a mews structure appended to the back of the original building will be demolished entirely. The new accommodation will comprise three apartments of two bedrooms each and a fourth containing three bedrooms.

Returning finally to Alice Meynell and her work, I close with a couple of passages that relate to her experience of London life—a topic she often touched upon in her essays for various London-based magazines, and more extensively in an 1898 book entitled London Impressions (where her text accompanies pictures by the artist William Hyde). I shall give one sample of prose and one of poetry, both included in the new anthology.

Here is an extract from the beginning of an essay on ‘Cloud’, published while the Meynells were living at Palace Court. Members of the Bayswater Residents Association may be interested in what is now an unorthodox view of the sash window.

During a part of the year London does not see the clouds. Not to see the clear sky might seem her chief loss, but that is shared by the rest of England, and is, besides, but a slight privation. Not to see the clear sky is, elsewhere, to see the cloud. But not so in London. You may go for a week or two at a time, even though you hold your head up as you walk, and even though you have windows that really open, and yet you shall see no cloud, or but a single edge, the fragment of a form.

Guillotine windows never wholly open, but are filled with a doubled glass towards the sky when you open them towards the street. They are, therefore, a sure sign that for all the years when no other windows were used in London, nobody there cared much for the sky, or even knew so much as whether there were a sky.

She is not always, however, so pessimistic about London life. The poem ‘November Blue’, also written during the Bayswater years, starts off by deploring the lack of blue sky in modern London, where pollution blots out that ‘heavenly colour’ and even the blue-less sky is glimpsed only in the narrow gaps between closely packed buildings; but the second half of the poem seems to make a virtue of this defect. It depicts vividly the glow—a blue glow, she tells us—of a November evening by gaslight in late-Victorian London. It isn’t the natural blue of the sky, but it’s blue all the same, the ‘heavenly colour’. That is an effect one would like to have seen.

November Blue

—ESSAY ON LONDON

O Heavenly colour, London town

Has blurred it from her skies;

And, hooded in an earthly brown,

Unheaven’d the city lies.

No longer, standard-like, this hue

Above the broad road flies;

Nor does the narrow street the blue

Wear, slender pennon-wise.

But when the gold and silver lamps

Colour the London dew,

And, misted by the winter damps,

The shops shine bright anew—

Blue comes to earth, it walks the street,

It dyes the wide air through;

A mimic sky about their feet,

The throng go crowned with blue.

Selected Poems and Essays of Alice Meynell, edited and introduced by Alex Wong with a preface by Laura Mulvey, is published by Carcanet. Paperback, 216 pp., £16.99.

From the back cover:

Alice Meynell was a major British author of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is the first anthology of her verse and prose to be published for over seventy-five years. Meynell was highly regarded both as a poet and as a writer of essays and was seriously proposed for the laureateship on two occasions. G.K. Chesterton said of her that she ‘never wrote a line, or even a word, that does not stand like the rib of a strong intellectual structure; a thing with the bones of thought in it’.

The present selection includes the early romantic poems of yearning, full of poignant surprises, and the terser, less personal poems of her maturity. Also included is a broad sample of Meynell’s literary essays, in each case a careful work of art. They include reflections on literature, culture and the natural world, nuanced observations on childhood, and moving defences (both specific and general) of women against trespasses on their dignity.

This selection, made and introduced by Alex Wong, also includes an appreciative preface by the renowned feminist critic and theorist Laura Mulvey, who is the author’s great-granddaughter.